Local and global at the same time:An interview with Rotterdam gallerist Wilfried Lentz.

Local and global at the same time: An interview with Wilfried Lentz about the changing city landscape and the art scene of Rotterdam in the past 30 years. His gallery has been relocated three times to various locations in Rotterdam in the past 10 years. We talked about art, his gallery concept, the changing art market and whether art has become a repetition of saleable standards.

You opened the gallery 10 years ago. How has the city changed? How has the art world changed over time?

I have been living in the city since 1984. I was not professionally in the art world in Rotterdam at that time, but I was visiting galleries and museums so I have quite a good idea of how things have changed in the past 30 years. What you can see immediately is that the city has been gentrifying very fast. More and more people can buy expensive houses and it has an effect on affordable housing as well. You can see this especially in the city centre but also in the south. Sometimes when I look at the newly built high-rises with luxurious apartments, for example, at Leuvehaven and Kop van Zuid, I wonder who is living there. I assume someone who can afford to live there could be a potential client for contemporary art. But the art scene I would say has stayed pretty much the same actually. There are around the same number of galleries as 20–30 years ago; the owners have changed and moved to other areas though. In the 90s, most of the galleries were in the Witte de Withstraat, then they moved to the west. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen was quite significant in the 80s and 90s. It has lost its importance in the last 15 years when it comes to contemporary art, and is now also less visible because of the renovation of the building. Perhaps now there are more institutions than there used to be, such as the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, which was founded in 1990. Artist residencies like Foundation B.a.d or Kaus Australis were already here in the 80s. The focus of the institutions and also the artist initiatives hasn’t changed that much either. In the 80s, or even in the 70s, there were already outstanding art events because of great curators who were up-to-date on contemporary art developments at that time. There was always an international connection to the rest of the word; it was never provincial. It is also the case now with some curators, who are very well informed internationally. In the past five years, Kunsthal Rotterdam and TENT have been exceptional, which obviously has something to do with the directors. Charlois, in the south of Rotterdam, is becoming a little hub, with artist initiatives such as Rib, Peach and Shimmer. The week of Art Rotterdam has turned into a festival atmosphere where people celebrate. But on a daily basis, institutions are much more important to the city than short events.

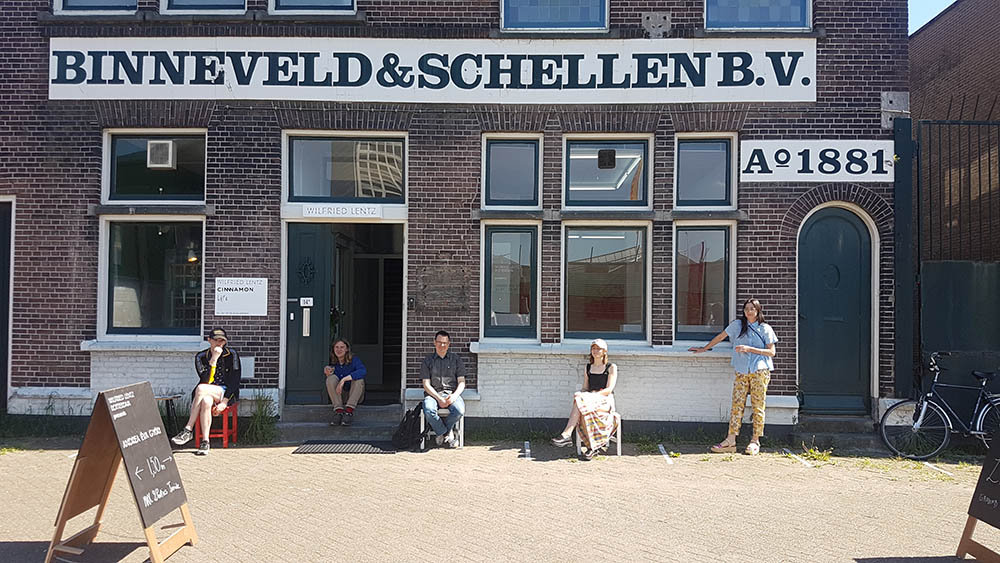

Your first location was in the city centre; then you moved to the Justus van Effen complex, the former bathhouse where you shared the building with the non-profit art space, A Tale of a Tub. Since last October, you have been based near the harbour in the former headquarters of the trading company, Binneveld & Schellen, which building is currently owned by Stichting AVL Mundo. Why did you decide to move there? How is the change? One of your colleagues, CINNNAMON gallery, has also moved there recently.I started my gallery in the Groot Handelsgebouw in 2008. It was a very obscure place but artists loved the shows there. It was in the middle of a huge building and was hard to find and the windows faced the courtyard. I am always looking for special architecture and a special connection to the environment. This was the case, both with Groot Handelsgebouw and Justus van Effen complex, as well as here. Justus van Effenstraat was a kind of next step in the growth of the gallery. In Groot Handelsgebouw, I didn’t have a decent office and the winter was super cold. I needed a decent office and a space for an assistant. I saw Justus van Effenstraat was for rent but it was too large for me alone, so I asked a few curators if they wanted to join me and that became the Tale of a Tub. I think collaboration is a good thing and, in this case, it made sense for several reasons not to go there alone. The intention was that if the space is fantastic, the architecture is appealing and there is an interesting and larger programme, more people will come. But I overestimated the possibilities of the venue. I had to programme two floors and it was a bit too much for Rotterdam and The Netherlands. At the same time, Tale of a Tub is an independent art space and has a different focus than a gallery. These were the main reasons for starting to look for another place, first in the city centre. I hoped for a space near one of the institutes; I also approached them. The centre is very difficult - the rents are too high and interesting venues are rare. I had no gallery space for two months. At a certain point, I called Joep van Lieshout and I asked if he had some space left because I knew about his development. I had also had enough of corporate landlords—I didn’t have a very good experience with them. The fact that Joep van Lieshout is doing this development means the rent serves a better cause towards realising his plans, rather than just paying it to an anonymous landlord. This was also the reason to call him. If it had been a strategic decision, I would have preferred the city centre.

I had already been talking to Pieter Dobbelsteen, director of CINNNAMON a year earlier about starting something together so he joined later. I strongly believe in joined forces. If you are a small gallery - as most of the galleries are in the Netherlands - and not like these huge mega-galleries with an extensive audience, then it is better to do something together. When people can go from one point to the other within walking distance, that is the best, like the galleries in the west of Rotterdam. This area is a bit rough, which is more in line with contemporary art. It is also home to many creative initiatives like the Keile Bar, Weelde or Kunst and Complex.

Recently, we have also set up an art space in the building called LIFE. Actually, Ash Kilmartin, who set it up, was my former assistant at Justus van Effenstraat. I knew she wanted to do something with artists’ jewellery, books and objects so I invited her to programme the little space next to mine. All these developments haven’t just come out of nowhere; we had already been talking about it for a long time as you can see.

What are the most challenging and rewarding aspects you have faced as a gallerist? What do you find exciting about your work?

What I love the most is making shows. That is really my thing. When I started the gallery, my dream was to have a beautiful little shop and sell the most beautiful things in the world. It’s a very romantic idea in a way but that’s what drives me. I see the show as the final edit of a production process. The artist produces their work, it gets delivered to the gallery and then you have to think about how to show it in the most interesting way possible. It’s a dialogue and that is what I love the most - the last stage in the production, developing a show together with the artist. It’s not just hanging paintings on the wall. If you look at my earlier shows I had in the gallery, there was always a kind of element in the set-up which was not usual - something extra, an experiment. We always do our best to present the work in the best way possible. I also try to get collectors involved in the process but it is difficult.

Giorgio Andreotta Calò, Senza titolo (La fine del mondo), 2017 / Untitled (The End of the World), 2017, Installation view at Italian Pavilion 57th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, Photo: Roberto Marossi

You mentioned in another interview that for you, being a gallerist is more about production and distribution rather than selling. You had a substantial investment in the production of the installation that one of your artists, Giorgio Andreotta Calò, made at the last Venice Biennale. How exactly do you support your artists?

Venice Biennale was a special occasion. I often invest a lot in gallery shows - like now, framing, carpet, pedestals etc. - not that many galleries are doing this I suppose. But it is also something to do with my interest in making shows and being part of the production and presentation. I think it is something I am good at. I call it “the final edit” or “final cut”. That’s the moment when you show it to the audience. I always try to help artists with what I am naturally good at. Also, it is easier for me to sell the work if you are already involved in the development. The production of the installations at the Venice Biennale was a bit different for us. The gallery was more involved on a financial level. There were many different interests, a lot of parties were involved - the curator, the biennial organisation, sponsors, collectors, the artists etc. - which makes it more complex. We raised a significant part of the financial need to make the work possible. It was the case with Giorgio but also with another artist, James Beckett. We sold editions of his work in order to raise money for the production of his installation at the Venice Biennale 2015. We didn’t get any profit from the editions. It was for the benefit of the work at the Venice Biennale. For the Dutch pavilion in 2017 with Wendelien van Oldenborgh, the gallery raised a considerable amount of money from donors but also the gallery invested in the work.

You work mostly with international artists - five of your 14 artists are from the United States. Do you follow contemporary art developments and artists from these countries?

It has more to do with the subject rather than the artists. It comes naturally to me, to follow what artists are doing all over the world and the subjects they are interested in. Indeed, it looks as if there is a specific orientation to the US, but there is no particular reason, I have always followed art internationally. The United States is a large country with lots of good artists, so maybe that is a reason. If you aim for quality, why don’t you follow artists from all around the world and not limit yourself to The Netherlands? There are several ways to find out what is going on, mainly by visiting big shows and biennales and a focus on smaller venues with solo presentations. There you can find new talent. Large exhibitions and solo shows are more content-driven, more about the work and much less about the commercial aspect. Art fairs focus on sales and there are often distractions around.

Liz Magic Laser, Primal Speech, 2016, Installation view at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam, september 2017, Single-channel video, LED display, polyurethane foam, vinyl, thread, Velcro, mirrored dibond, porcelain, wood, Plexiglas, felt, wire, synthetic fiber batting, grey carpet, 760 x 314 x 182 cm. Photo: Paula Winkler

How would you describe your relationship with your artists? What is the most important aspect for you?

The pleasure of collaboration and the conversations are important. At a certain point, it becomes friendship. There are always three elements involved: the personal, commercial and the artistic aspect. I always say two of the three elements have to be positive, otherwise it doesn’t work.

Which artists have you been working with for the longest and for how long?

Matts Leiderstam. I had my first show with him 12 years ago.

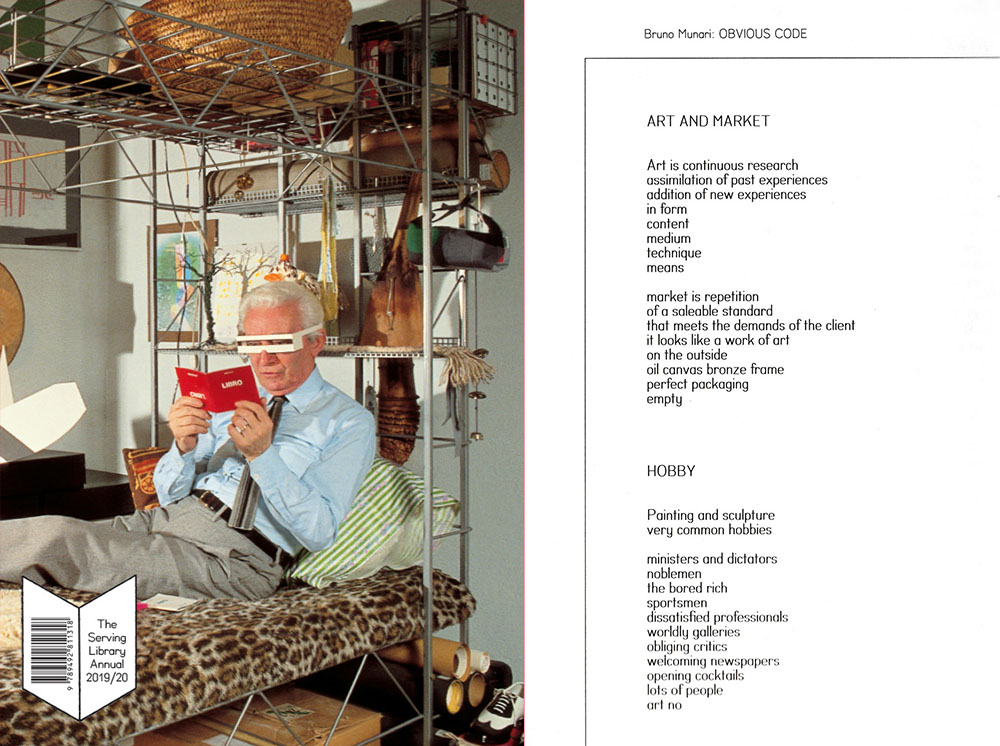

Before the interview, you shared a text with me from Bruno Munari that you wholeheartedly support: “Art is continuous research | assimilation of past experiences | addition of new experiences | in form | content | medium | technique | means | market is a repetition | of a saleable standard (...)” (Munari, B. 1971: Obvious Code, p.70) Can you comment on this?

I shared this quote because Bruno Munari, more than fifty years ago, made an interesting distinction between art and the market. Contemporary art has become a kind of commodity in the last 10 years and that primarily has to do with the market. Munari gives a nice definition of art versus the commodity which is helpful in analysing what is currently happening. At the moment, the super-rich people determine what happens in art, at least in some part of the art world. What is happening is that the peers of the “very rich” are also the “very rich” and most people tend to buy the same work of art as their peers. Unfortunately, it is not always a guarantee of quality, but galleries supply this demand. It is also a misunderstanding to look for the same satisfaction when buying art as when buying a dress or shoes. Some people confuse these two: the satisfying experience of purchasing an artwork and the experience of shopping. But if you have no knowledge of contemporary art and you have a lack of visual literacy or you just buy what others buy, there is a good chance you buy kitsch or a commodity. Of course, I generalise, but that’s what’s happening. There is a lot of kitsch in the market and it’s becoming infertile. Here comes Munari’s quote when he says the market has become “repetitive standards”. The good side is that more money comes to the artists.

Munari, B. 1971: Obvious Code, The Serving Library Annual, Issue 2019/20, Roma Publications, 2017

How do you describe a great work of art?

It is difficult to describe a great work of art if you don’t have a background or education. It’s like tasting wine. If you’ve never tasted good wine and gone through a progress by yourself, you need to invest time and energy in it. It’s not only a matter of taste - it’s a matter of progress and literacy.

What do you look for in an art piece? What do you think about the relationship between art and technique? Do you think art has to be innovative?

Not necessarily, of course. I have an affinity towards innovative artworks. I like artists who are able to shift borders or use new techniques in an interesting way. It is something that fascinates me. Some artists are really inventors - I love that. It is a personal interest. I always compare the first experience of a good artwork to meeting someone for the first time who you later become friends with; you feel a recognition right away.

Lots of artist you work with use forms of appropriation. Can you comment on that?

I don’t know why I like that approach. I can’t explain. It’s personal.

Karel Martens, Beach cabin E6/10, 2017, Customised modular beach cabin 220 x 200 x 200 cm Unique (KM2017-02), Installation view Colours on the Beach, 2018 at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam. Photo: Tor Jonsson

Do you have an exhibition that is especially memorable or a project that you are especially proud of?Yes, there are several. An extract of all of my past exhibitions are available on the gallery website. I liked the group show “Not Created By A Human Hand” in 2010, which opened on Christmas Eve. Also, the text is fantastic—written by an academic, Alena Alexandrova. She did her PhD about that kind of imagery. The “Mountainshow” in 2009, a group exhibition with works by Marc De Blieck (BE), Jules Spinatsch (CH), Carleton Watkins (USA), Rossella Biscotti (IT) w/ Jacob Kirkegaard(DK), Matts Leiderstam (SE), and Aldwin van de Ven (NL). And another one in 2010, “Ghost Transmissions”with Carl Michael von Hausswolff worked out very well. We have had several solo shows I also liked.You are a collector yourself. Do you have a favourite piece in your private art collection?They are all love babies. Each artwork speaks to me differently. One more than the other that is true. I cannot tell which one is my favourite.

Andrea Éva Győri, Bold Head With Tongue, 2020, Installation view at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam. Photo: Robert Glas

Andrea Éva Győri, Transparent Body, 2019, pencil and gouache on paper, 29,7 x 42,0 cm, AG2019-05

Your current show is “Bold Head With Tongue”, a solo show by the Hungarian artist, Andrea Éva Győri, who currently lives in Rotterdam. Her latest painting and drawing we can see at the exhibition explores female sexual experience. She is not one of the artists you currently represent. How did you meet her? Why did you choose her? Can you tell a bit more about it?I saw her work for the first time at the Jan van Eyck Academy more than a year ago. I liked the presentation but I forgot about it for a while. We bumped into each other at an opening not long ago, and I found out she lives in Rotterdam. She asked for a studio visit where I learned more about her work.Can you tell a bit more about the exhibition and the choice of the presentation. Did you work on the “final cut” together with Andrea? What choices did you make?

We designed the space for the drawings. We used pedestals to present them in a more intimate way. My suggestion was also to place the paintings on columns in order to create a more coherent space. A carpet with a prime colour is something that Andrea had already used before. I like the contrast of the red carpet and the white pedestals. As the white pedestals blend in with the white wall they create a negative shape on the red carpet. If you stand at the back side of gallery and look towards the window, the drawings become invisible from that point of view and the gallery transforms into a pure architectural space. I was always interested in using the gallery as an architectural background for an exhibition and creating a dialogue between the space and the artwork. All the other artists I work with are also conscious about this element and you can notice it in earlier exhibitions we have made. I love giving the viewer a special experience when they enter the gallery.Your gallery is open now. What has been your experience during the Corona crisis? Has your interaction changed? How is it different from before?

I think it’s good that people make reservations so they really take time to look around and they know there are two other exhibitions to visit here as well. I think it’s not that much has changed in terms of collectors. People travel less but that will come back. I participated in one of the online selling platforms because you can reach a large international group of people. It worked out well. I think in the end it will go back to where it was before but at a slower pace; that is my instinct.

How about your artists — how is it for them now?

It’s different for each one of them, like for all of us. For some, it’s more depressing; others keep doing what they've always done. I know some of my artists in NY were more concerned about the development but the situation in the US is harder than here.

An interesting article came out a couple of week ago in deVolkskrantabout whether the art should be more locally rooted after Corona crisis. Many events have been cancelled. International travels are restricted, which means the artists cannot be at events, and also artworks can't be shipped to exhibitions. Has the era of cultural regionalism arrived? What do you think about that?

Local was already important, at least in the Netherlands. Most people were already trying to find out what was going on in their immediate environment. If you look at the collectors, most of them are looking within a very small circle. They don’t go abroad a lot. Some do, of course, but I would say the majority stay in the Netherlands. Which is fine. When it comes to the gallery, I have already started to slow down a bit, stay here and do less shows a year compared to what we did in the early years. Do something special and keep it for a longer time; that is my strategy. I think that it makes more sense now as well. Also, if the show is on for longer periods, people can have a second chance to visit. Sales, in fact, run in parallel to the shows. We also sell artworks that are not included in the current exhibition.

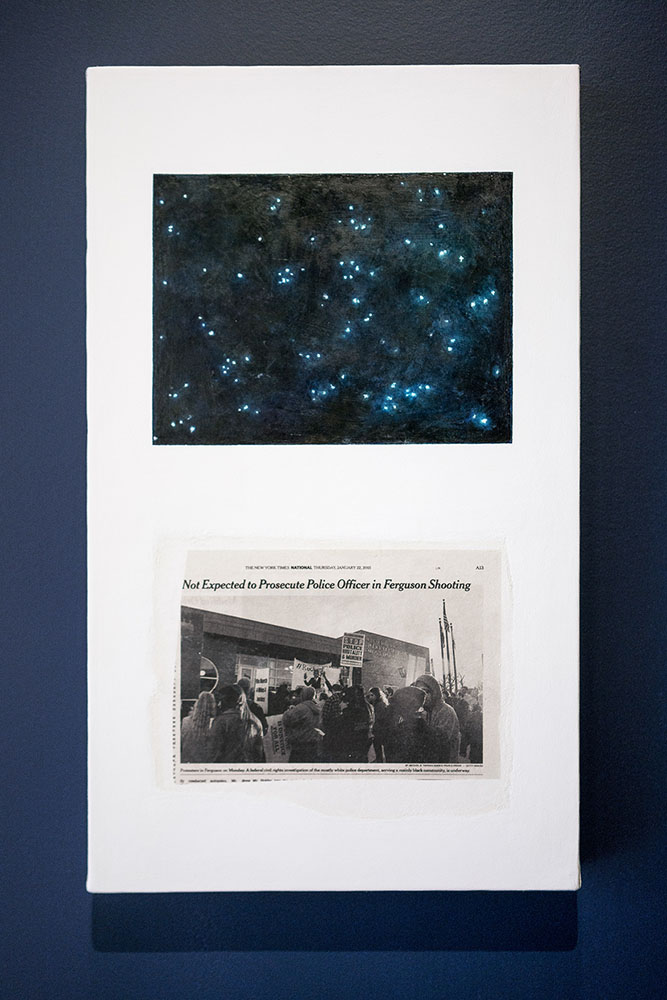

You are participating in the nationwide project called Unlocked/ Reconnected with the artwork “Nocturne” by Doug Ashford. Why did you choose his artwork for this project?

Doug painted this piece three years ago. It’s about the incident of a shooting of a black boy in Ferguson in August 2014. Doug made a painting of the sky as it looked like at that moment at that place. Below the painting there is a newspaper article cut out from The New York Times from January 2015, which is five months after the incident. The article talks about the persecution of the officers and the investigation of the police department. I love the way he made this painting. Seeing the sky gives you a larger view than what is happening on Earth. It gives a different perspective - a kind of larger idea of truth. It’s a beautiful idea.

13 July, 2020

Doug Ashford, Nocturne

2017

Oil and archival mounted inkjet print on canvas

50 x 30 cm

Wilfried Lentz RotterdamKeileweg 14a, 3029 BS

'Bold Head With Tongue'

Andrea Éva Győri, solo exhibition

21 March - 29 August 2020'Film Stills From 214322'

Aimée Zito Lema12 September - 7 November 2020 Open:

Thu - Sat 14.00 - 18.00

Coronavirus Update: Visiting in time-slots of one hour can be booked by clicking here. Outside these hours open by appointment.